Conservation of the T. R. Peale Butterfly and Moth Boxes

|

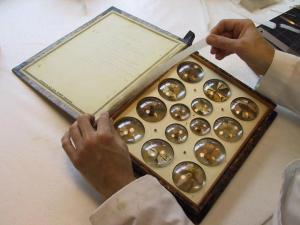

Catharine Hawks, a professional conservator whose specialty is in natural history collection materials, treated all the Peale boxes. By researching Peale's methodology as he had written it up in 1864, and performing simple analytical tests, Ms. Hawks determined the construction techniques and materials used in the boxes. This information allowed her to develop a plan as to how the boxes could be opened for cleaning and repair with the minimum potential for damage. Before any work was done, each box was carefully examined, measured and described. Notes were taken on the condition of the covers, end papers, bindings, glass, the corks and pins that hold the specimens, and the specimens themselves. The adhesives and sealers used were recorded, as were any inscriptions on the spines of the book boxes. |

|

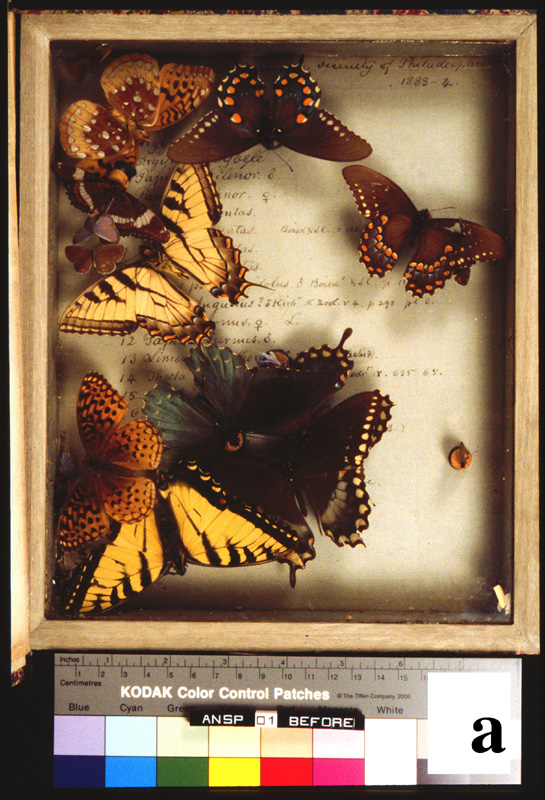

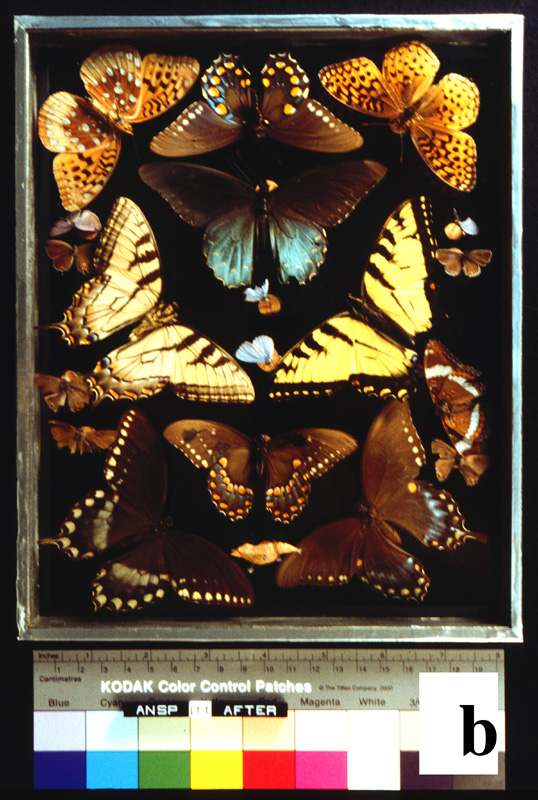

In most cases, the inner glass box containing the specimens was separated from the outer book binding. The book binding was then sent off to be treated by book and paper conservators at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA). Documenting every phase of the process with notes and photographs, Ms. Hawks then opened the boxes and cleaned all accessible surfaces. Repairs were made to damaged specimens whenever possible. Fragments of specimens that were loose and not associated with a specific specimen were gathered up and placed in envelopes to remain with, but not inside the boxes. While the boxes were open, they were photographed in their entirety, and each specimen was individually photographed and measured. The cleaned and repaired boxes were then re-sealed. All materials used by the conservator for cleaning, repair and reassembly of the boxes have long term stability (they will not break down over time, or release any damaging vapors) and reversible using safe solvents (water or acetone). The boxes were then replaced in the cleaned and repaired book bindings. Finally, each box is now housed in a special protective, individually fitted case. These cases contain special enclosures for the parts of the boxes and specimens that were kept separately from the reassembled boxes. This material includes fragments of the specimens themselves, pages of specimen identifications that were not glued into the bindings, as well as shims and tin sealing material that were not replaced during the reassembly process. The boxes in their protective cases and all the documentary materials created during the project are now stored in new tightly sealing cabinets which will shield them from fluctuating environmental conditions, damaging insects, dust and theft. Some "worst case scenarios" included boxes such as the one shown in the photograph to the right (a). Virtually all of the specimens were loose due to dessication or other failure of the adhesive used to attach the cork pinning bases to the rear glass. Repairs and reallignment of specimens in boxes like this one were often quite a challenge and in some cases where there were numerous conspecific individuals with extensive damage, reassociation of loose appendages was not possible. After restoration (b), the arrangment of specimens in the above box approximates the original positioning of specimens intended by Peale. Specimen arrangement was based on evidence of adhesive residue on the rear glass panel (used to position detatched cork bases) and comparison with the orientation of specimens in other intact boxes.

|

|